Your Cart is Empty

The misty, forested highlands of Central America are today known as one of the world’s best coffee regions. Honduras is currently the region’s leading coffee producer, followed by Guatemala, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and El Salvador. The tropical region features plenty of prime coffee-growing areas, where cool temperatures at relatively high elevations and rich, volcanic soil allow the seeds to consolidate incredible flavor.

Central American coffees, often called “Centrals” in the coffee business, are typically acidic with a bright flavor, sometimes incorporating nutty or earthy notes. Embedded within the history of global trade and European colonialism, the story of Central American coffee is similar to that of coffee in other places. Here’s how the Central American countries south of Mexico got their coffee chops (we’ll cover Mexican coffee in another post).

Beginning in the early sixteenth century, Spain conquered much of Central America. The region was home to hundreds of Indigenous societies, including descendants of the Mayan Empire, the strong Lenca nation in western Honduras, and the Ngäbe and others of the Chibchan culture in today’s Panama, Costa Rica, and Nicaragua. By the late eighteenth century, Spanish andmestizo (mixed-race) colonists in Central America were increasingly restless under the reformed grip of the Spanish monarchy. Like other colonial populations in the hemisphere, many in Central America contemplated independence.

Meanwhile, over the course of the eighteenth century, the coffee plant (Coffea arabica) arrived in the Caribbean. Coffee is not native to the Western Hemisphere, having evolved in the highlands of Ethiopia. A coffee shrub arrived in the French sugar colony of Martinique in the early 1720s, and French colonists planted coffee trees across the island sugar colonies.

By the 1780s, the French colony of Haiti—then the richest European colony in the Americas—was supplying half the world’s coffee. The importance of the coffee trade to the French empire and the intolerable conditions of coffee plantations in Haiti directly contributed to the Haitian Revolution of the 1790s, the only successful revolt by enslaved people in the hemisphere.

In the years leading up to the Haitian Revolution, coffee plants in the French Caribbean were brought to the mainland and planted in Mexico, Costa Rica, and Nicaragua. These were the genetic ancestors of today’s Central American coffees.

In 1807, Napoleon invaded Spain, forcing the Spanish king to grant concessions to agitated Central American colonists. But after Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, the Spanish king revoked these measures, prompting wars of independence in Central America. A drawn-out struggle first produced several versions of a unified Central American state, which eventually split into the countries we know today: Mexico (1821), Nicaragua (1838), Honduras (1838), Costa Rica (1838), El Salvador (1841), and Guatemala (1847). Panama remained part of the South American state of Gran Colombia until the construction of the Panama Canal brought its independence in 1903.

With the decline of the indigo dye trade in the early 1800s, the newly independent Central American states turned their attention to coffee as a new export commodity. From the 1830s onward, coffee farms sprang up in El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, and exports of Central American coffee to the United States began in 1840. Central American nations had the environment, the plants, and the knowledge to maintain a large coffee industry; plus, there was great worldwide demand and a supply shortfall after Haiti’s coffee plantations were destroyed in the revolution. The major obstacles were the lack of a large labor force to furnish that supply, and the infrastructure to get the coffee to market.

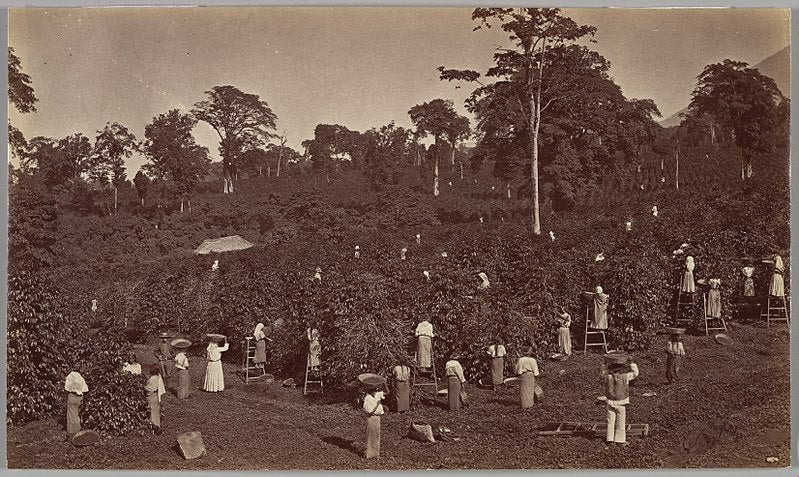

By the 1870s, the owners of large coffee estates, known as "caudillos,"controlled the governments of newly independent Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala. Determined to grow the coffee industry, they passed laws that privatized Indigenous and church land (so it could be converted to coffee plantations), forced Indigenous populations to labor on coffee farms, and funded development of essential state institutions (like security forces) and infrastructure for the coffee industry.

These policies brought thecaudillos unparalleled wealth and power across the region but also resulted in widespread displacement, impoverishment, and suffering, especially among Indigenous populations. It’s no surprise, then, that the governments of El Salvador and Nicaragua spent much of the late 1800s putting down uprisings. The long history of inequality and political instability in those two countries can be traced directly back to the coffee policies of Central American caudillos.

The caudillos also welcomed the foreign investment necessary for coffee infrastructure. The New York-based Panama Railroad Company finished a line across the isthmus there in 1855, allowing for easier export of more Central American coffee. In Costa Rica, where coffee farming developed along more egalitarian lines initially, caudillos also used foreign investment to increase local control. Small Costa Rican coffee farmers became trapped in debt cycles to British banks, and many ended up selling their land to large coffee estates to get out of debt.

By the early twentieth century, Central America had eclipsed the West Indies as a primary supplier of coffee to the United States and Great Britain. A 1912 report by Harry C. Graham, a researcher with the US Department of Agriculture, outlines just how important coffee was to Central American economies. It was noted as the “principal crop” of Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua, and was just starting to become favored in Panama and Honduras. In Costa Rica, meanwhile, Graham notes that by 1912 “nearly all lands suitable for coffee culture have been taken up,” with most of the product going to the UK. Overall, Central American nations sent a total of 52 million pounds of coffee to the United States in 1911.

This relationship meant that coffee played a role in the various US interventions during the twentieth century. This was especially true during the 1930s, when worldwide depression, foreign influence, and agricultural overproduction led to labor strife in Central America.

American troops occupied Nicaragua from 1927-33 to protect the interests of American fruit companies there, and the Nicaraguan government drastically expanded coffee production to offset low prices. This expansion removed thousands of poor Nicaraguans from their land, and these farmers joined military officer Augusto César Sandino’s army, theSandinistas. Sandino’s army conducted guerrilla warfare and sabotage against US fruit plantations and occupied the coffee estates. They were eventually defeated by a US-backed authoritarian regime that ruled Nicaragua for the next 40 years.

Falling coffee prices also influenced revolt in El Salvador, where 1.5 million people depended on the coffee trade. As the industry collapsed during the Great Depression and workers turned to unrest, the wealthy coffee oligarchy in El Salvador turned to an authoritarian government to crush the uprisings. In 1932, the Salvadoran government carried out what is now known as “La matanza” (the killing), murdering 30,000 people, most of them Indigenous workers fighting exploitation in the coffee sector.

Agricultural unrest and US imperialism plagued many in Central America for the duration of the twentieth century, with theSandinistastruggle only the most well-known of the regional conflicts. By the 1960s, however, many Central American governments had set up national coffee associations to better regulate the coffee industry and control some of the volatility. Although the era of direct US intervention has ended, the legacy of imperialism and authoritarianism in Central America means that most coffee farmers in the region still face uphill battles to make a decent living.

Central America today supplies 8.8 percent of the world’s coffee, most of which is cultivated by small-scale growers. But since the late 2010s, the industry has suffered a downturn due to the resurgence of the leaf rust disease, introduced from Brazil in the late 1970s. The problem is exacerbated by more frequent hurricanes and other climate disasters that displace the laboring population and cause outbreaks of rust. These external challenges make growing coffee more expensive, so debt is another factor driving Central American coffee farmers to sell their land and migrate north to Mexico or the United States.

At Harbinger, we’re fully aware of the troubled history and present of the coffee industry around the world. That’s why we take care to work with select importers who procure the finest Central American coffees from growers who are paid a fair price. By supporting hard-working coffee farmers there and elsewhere in Central America, Harbinger is doing our small part to further responsible coffee sourcing as we seek to provide our customers in Colorado with the world’s finest cup. Stop by and try some today.

Sources:

Maytaal Angel, Gustavo Palencia, and Sofia Menchu, “Coffee crisis in Central America fuels record exodus north,” Reuters, December 8, 2021.

Central American Coffee Info, Sagebrush Coffee.

“Coffee Report, Central America,” Regional Cooperative Program for the Technological Development and Modernization of Coffee Cultivation in Central America, Panama, Dominican Rep and Jamaica, November 2021.

“Coffee Rust,” American Phytopathological Society.

Daniel Faber, Environment Under Fire: Imperialism and the Ecological Crisis in Central America (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1993).

Harry C. Graham,Coffee: Production, Trade, and Consumption by Countries, US Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Statistics Bulletin no. 79 (1912).

David J. McCreery, “Coffee and Class: The Structure of Development in Liberal Guatemala,” Hispanic American Historical Review, 1976.

Jefferey M. Paige, Coffee and Power: Revolution and the Rise of Democracy in Central America (Harvard University Press, 1997).

Image Credits:

Wikimedia Commons

Encyclopedia Britannica

Adam Keough

Sven Hansen